(Click to Enlarge)

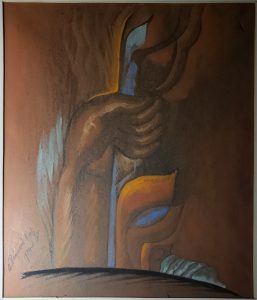

Gouache on paper or board

12 7/8 x 10 3/4 visible inches

Framed and matted behind glass in period frame 20 1/4 x 17 1/4 inches

Brilliant colors with original indention upper right. Right and left lightened area is glass reflection.

Signed A. Raymond Katz 1920 lower left

Chicagoland origin

An early Chicago modernist painting by Hungarian Jewish American artist Alexander (A.) Raymond Katz. Appears to be symbolizing the struggles of the African Americans. Katz entered the Art Institute of Chicago in the early 1920s. Below contains his biography and an overview of Modernism in the Visual Arts.

Alexander (A.) Raymond Katz

b. Kassa, Hungary, 1895–d. New York, NY, 1974

A. Raymond Katz was born in 1895 in Kassa, a military town in northern Hungary. His father was a tailor who made military uniforms. After the young artist started selling his work in Kassa, his father permitted him to study art in New York. He came to the United States in 1909 at age 14 (his given first name, Sandor, was anglicized to Alexander) and supported himself in New York with a variety of odd jobs. Katz eventually found employment in a lithography shop in Chicago producing war posters, earning enough money to build a house and bring his family to the United States.

After the war, Katz traveled to the West Coast and Canada, arriving back in Chicago rich in experience and in need of a paying occupation. He took a job at the Barron Collier company designing car card advertisements, but quit in 1922 to enroll at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. He supported himself with jobs in the burgeoning motion picture field, ultimately as the director of the art department of the Balaban and Katz (no relation) theater empire, where he oversaw the decoration of the movie palaces of the 1920s. In 1927, Katz and his family (he married in 1924) traveled back to Kassa where he pursued his first love, fine art. He reconnected with his Jewish heritage and brought back to Chicago many images of Jewish life. Although he continued to do commercial work throughout his career, he increasingly began to explore Jewish themes and was the recipient of numerous commissions for synagogues all over the country, creating stained glass windows, murals, reliefs, sculptures, and decorative items for them. He set up a studio in his apartment building and opened an office in the tower of the Auditorium Building that also housed the Little Gallery, an important venue for progressive art in the city, which he operated until 1933.

Katz also explored the aesthetic and philosophical interpretations of Hebrew letters, as seen in the woodcut Moses and the Burning Bush, which he submitted to the portfolio, A Gift to Birobidjan in 1937. Hebrew letters are integrated into the image: the first initial of Moses’s name crowns his head; the first letter of the name of God appears inside the flame; and his staff is topped by a letter.

During the Depression, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright urged Katz to become a muralist and in 1933, he was one of eleven artists chosen to create murals for the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, where his enormous secular work, O.K., was installed in pavilion three of the General Exhibits Building along with a series of murals addressing Jewish themes in the Hall of Religions. He won the competition for best poster for the fair in 1934. In 1936, he was commissioned to paint murals representing the Ten Commandments, for the Loop Synagogue in Chicago, then thought to be the first murals in an Orthodox synagogue.

In addition to his work for Balaban and Katz, he served as director of the poster department at Paramount Studios (1926–31), and the director of posters for the Chicago Civic Opera (1930–33), developing his graphic talents as well as his fine arts skills. His large gouache on paper, Untitled (Radio performer), reflects his background in theater, offering a behind-the-scenes view of the radio business. It is an animated portrait of a sound technician in front of a microphone, shooting a gun (presumably with blanks) and surrounded by paraphernalia of the sound effects trade. Evidence of the close relationship between his commercial work and his pursuits as a painter are found in an illustration from The Chicagoan (July 1933), a short-lived periodical that employed Katz frequently as a graphic artist. His drawing shows a family in front of their radio from which emerges a fantastic variety of entertainments in an overall pattern stylistically similar to that of Untitled (Radio Performer).

Like many artists in the 1930s, Katz participated in the government-supported arts projects. In 1936, Katz won the commission to paint the mural, History of the Immigrant, for the post office in Madison, Illinois, from the Treasury Department, the most prestigious of the projects. His style and subject matter, like that of many of his contemporaries, reflected the mandate to represent “the American Scene.”

His oil painting, Chicago Street Scene, 1936–42, is one of a series of images of Chicago’s alleys that Katz produced during the Depression. Highlighting the small-town camaraderie that was fast disappearing in 1930s America, Katz also alludes to the poverty of the period in the peddlers making their way on foot with wheelbarrows and horse-drawn carts. The color scheme, brilliant and jarring in this representation of material austerity that extends to the leafless trees, lends a bit of optimism to the dark times. The idea that art could change the world was one that Katz subscribed to in images such as this one.

Katz moved to New York in the 1950s, and died in 1974.

Source:chicagomoderndotorg

Susan Weininger and Lisa Meyerowitz

References

Bulliet, C. J. “Artists of Chicago Past and Present: No. 14: A. Raymond Katz.” Chicago Daily News, May 25, 1935.

Harris, Neil. The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Oakton Community College. A Gift to Biro-Bidjan: Chicago, 1937: From Despair to New Hope. Exhibition website, www.oakton.edu/museum/Katz.html.

Weaver, William R. “Sandor to You.” The Chicagoan (June 1934), 29, 57–58.

Weininger, Susan. “A. Raymond Katz.” In Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New, edited by Elizabeth Kennedy, p. 126. Chicago: Terra Foundation of American Art, 2004.

Yochim, Louise Dunn. Role and Impact: The Chicago Society of Artists, p. 248. Chicago: Chicago Society of Artists, 1979.

American modernism, much like the modernism movement in general, is a trend of philosophical thought arising from the widespread changes in culture and society in the age of modernity. American modernism is an artistic and cultural movement in the United States beginning at the turn of the 20th century, with a core period between World War I and World War II. Like its European counterpart, American modernism stemmed from a rejection of Enlightenment thinking, seeking to better represent reality in a new, more industrialized world.

Modernism in Visual ArtsThere is no single date for the beginning of the modern era in America, as dozens of painters were active at the beginning of the 20th century. It was the time when the first cubist landscapes, still-life and portraits appeared; bright colors entered the palettes of painters, and the first non-objective paintings were displayed in the galleries.

The modernist movement during the formative years was also becoming popular in New York City by 1913 at the popular Manhattan studio gallery of Wilhelmina Weber Furlong (1878–1962) and through the work of the Whitney Studio Cub in 1918. According to Davidson, the beginning of American modernist painting can be dated to the 1910s. The early part of the period lasted 25 years and ended around 1935, when modern art was referred to as, what Greenberg called the avant-garde.

The 1913 Armory Show in New York City displayed the contemporary work of European artists, as well as Americans. The Impressionist, Fauvist and Cubist paintings startled many American viewers who were accustomed to more conventional art. However, inspired by what they saw, many American artists were influenced by the radical and new ideas.

The early 20th century was marked by the exploration of different techniques and ways of artistic expressiveness. Many American artists like Wilhelmina Weber, Man Ray, Patrick Henry Bruce, Gerald Murphy and others went to Europe, notably Paris, to make art. The formation of various artistic assemblies led to the multiplicity of meaning in the visual arts. The Ashcan School gathered around realism (Robert Henri or George Luks); the Stieglitz circle glorified abstract visions of New York City (Max Weber, Abraham Walkowitz); color painters evolved in direction of the colorful, abstract “synchromies” (Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell), whereas precisionism visualized the industrialized landscape of America in the form of sharp and dynamic geometrization (Joseph Stella, Charles Sheeler, Morton Livingston Schamberg and Charles Demuth). Eventually artists like Charles Burchfield, Marsden Hartley, Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, Arthur Beecher Carles, Alfred Henry Maurer, Andrew Dasburg, James Daugherty, John Covert, Henrietta Shore, William Zorach, Marguerite Thompson (Zorach), Manierre Dawson, Arnold Friedman and Oscar Bluemner ushered in the era of Modernism to the New York School.

The shift of focus and multiplicity of subjects in the visual arts is also a hallmark of American modernist art. Thus, for example, the group The Eight brought the focus on the modern city, and placed emphasis on the diversity of different classes of citizens. Two of the most significant representatives of The Eight, Robert Henri and John Sloan made paintings about social diversity, often taking as a main subject the slum dwellers of industrialized cities. The late 1920s and the 1930s belonged (among many others) to two movements in American painting, Regionalism and Social Realism. The regionalists focused on the colorfulness of the American landscape and the complexities of country life, whereas the social realists went into the subjects of the Great Depression, poverty, and social injustice. The social realists protested against the government and the establishment that appeared hypocritical, biased, and indifferent to the matters of human inequalities. Abstraction, landscape and music were popular modernist themes during the first half of the 20th century. Artists like Charles Demuth who created his masterpiece I Saw The Figure Five in Gold in 1928, Morton Schamberg (1881–1918) and Charles Sheeler were closely related to the Precisionist movement as well. Sheeler typically painted cityscapes and industrial architecture as exemplified by his painting Amoskeag Canal 1948. Jazz and music were improvisationally represented by Stuart Davis, as exemplified by Hot Still-Scape for Six Colors – 7th Avenue Style, from 1940.

Modernism bridged the gap between the art and a socially diverse audience in the U.S. A growing number of museums and galleries aimed at bringing modernity to the general public. Despite initial resistance to the celebration of progress, technology, and urban life, the visual arts contributed enormously to the self-consciousness and awareness of the American people. New modernist painting shined a light on the emotional and psychic states of the audience, which was fundamental to the formation of an American identity.

Numerous directions of American “modernism” did not result in one coherent style, but evoked the desire for experiments and challenges. It proved that modern art goes beyond fixed principles.

Main schools and movements of American modernism:

· the Stieglitz group

· the Arensberg circle

· color painters

· Precisionism

· the Independents

· the Philadelphia school

· New York independents

· Chicago and westward

Georgia O’Keeffe has been a major figure in American Modernism since the 1920s. She has received widespread recognition, for challenging the boundaries of modern American artistic style. She is chiefly known for paintings of flowers, rocks, shells, animal bones and landscapes in which she synthesized abstraction and representation. Ram’s Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills, from 1935 is a well known painting by O’Keeffe.

Arthur Dove used a wide range of media, sometimes in unconventional combinations to produce his abstractions and his abstract landscapes. Me and the Moon from 1937 is a good example of an Arthur Dove abstract landscape and has been referred to as one of the culminating works of his career.[24] Dove did a series of experimental collage works in the 1920s. He also experimented with techniques, combining paints like hand mixed oil or tempera over a wax emulsion.

African-American painter Aaron Douglas (1899–1979) is one of the best-known and most influential African-American modernist painters. His works contributed strongly to the development of an aesthetic movement that is closely related to distinct features of African-American heritage and culture. Douglas influenced African-American visual arts especially during the Harlem Renaissance.

One of Douglas’ most popular paintings is The Crucifixion. It was published in James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones in 1927. The crucifixion scene that is depicted in the painting shows several elements that constitute Douglas’ art: clear-cut delineation, change of shadows and light, stylized human bodies and geometric figures as concentric circles in contrast to linear forms. The painting’s theme resembles not only the biblical scene but can also be seen as an allusion to African-American religious tradition: the oversized, dark Jesus is bearing his cross, his eyes directed to heaven from which light is cast down onto his followers. Stylized Roman soldiers are flanking the scene with their pointed spears. As a result, the observer is reminded for instance of the African-American gospel tradition but also of a history of suppression. Beauford Delaney, Charles Alston, Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden were also important African-American Modernist painters that inspired generations of artists that followed them. source:wikipedia and their referenced