(Click to Enlarge)

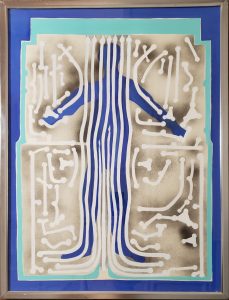

Suzanne Martyl Langsdorf “Martyl” (1917 – 2013)

Acrylic on Rag Board

40 x 30 inches

Title Circuit Prisoner en verso on tag which also includes artist name, medium, and Synapse Series designation

Original work related to the Synapse Suite,1974, which were produced into color lithographs, and are curated by the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago. The lithographs were published by the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Inc.

Fine condition

Chicagoland origin

Smithsonian: Name: Martyl, Also Known as Martyl Schweig Langsdorf Suzanne Schweig Suzanne Schweig Martyl Born St. Louis, MO, 1917 Died Schaumburg,IL, 2013 Nationalities American

Chicago Tribune: Martyl Langsdorf: 1917-2013 Joan Giangrasse Kates, Special to the Tribune (Chicago) Martyl Langsdorf, an artist married to a nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, created the widely known Doomsday Clock for the first cover of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. That June 1947 magazine put the clock, meant to depict how close the world is to nuclear holocaust, approaching 11:53 p.m., with midnight being the zero hour. “She understood the deep anxiety of the scientists in 1947, and the urgency of preventing the spread or use of nuclear weapons,” said Kennette Benedict, executive director of the Bulletin since 2005. “With the clock design, she gave the world a symbol that is even more potent today.” Mrs. Langsdorf, 96, died Tuesday, March 26, at a rehabilitation facility near her home in Schaumburg, after a lung infection. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was started in 1945 by a group of Manhattan Project scientists who formed an advocacy group to warn the public of the dangers of nuclear weapons and power. “It was a cause felt deeply by both my mother and father (Alexander Langsdorf Jr.),” said her daughter, Alexandra Shoemaker. “It was something they dedicated a good deal of their lives to, both personally and professionally.” During a career that spanned eight decades, Mrs. Langsdorf worked in various artistic media including painting, printmaking, drawing, murals and stained-glass design. Her works have been displayed in museums throughout the country, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Brooklyn Museum, Illinois State Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. She also had nearly 100 solo exhibitions in New York, Chicago, St. Louis, San Francisco and Los Angeles, as well as other cities. “From the time she was a little girl, she was a creative soul,” said her brother, Martin Schweig Jr., a photographer in St. Louis. “She’d push the borders, always looking for ways to create something new and innovative.” Born Martyl Suzanne Schweig in St. Louis, Mrs. Langsdorf grew up in a family that embraced the arts. Her mother, an artist and teacher, founded the Sainte Genevieve Summer School of Art outside of St. Louis. Her father was an acclaimed portrait photographer in St. Louis. “When we were children, my parents would invite some of the most gifted artists from around the country over for dinner,” Schweig said. “Looking back, it was quite amazing. But to us it was just normal.” Mrs. Langsdorf studied painting with Charles Hawthorne in Provincetown, Mass., when she was 11, and later with Boardman Robinson in Colorado Springs, Colo. She also played the violin and piano and contemplated a career in music, an idea that passed when she sold one of her first paintings to George Gershwin as a teenager when he was passing through St. Louis, according to her family. “What a stir that caused!” Schweig recalled. Mrs. Langsdorf received a degree from Washington University in St. Louis, majoring in the history of art and archaeology. In 1941, she married nuclear physicist Alexander Langsdorf, also of St. Louis. His work using caked plutonium at Washington University got the attention of Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, and in 1943, the couple moved to Chicago at the invitation of Enrico Fermi to join the Manhattan Project. The design of the Doomsday Clock, four dots and two lines, used a recognized object a clock and evoked the traditional imagery of the apocalypse (the cry at midnight) and the countdown to zero hour, or a military attack. “It’s such an intuitively tension-building image,” graphic designer Michael Bierut, who updated Mrs. Langsdorf’s design in 2007, told the Washington Post. “To be able to reduce something that complex to something so simple and memorable is really a feat of magic.” When the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon in 1949, the scientists who guided the Bulletin moved the hands four minutes closer to midnight. “The scientists decided to use it imaginatively as a metaphor,” Bierut, who is on the Bulletin’s board of governors, told the Washington Post. “To wed this almost childish cliche to this fear of the annihilation of the Earth, that’s really remarkable.” In 1953, the Langsdorfs bought the home of architect Paul Schweikher in what is now Schaumburg. An example of early midcentury modern design the home and studio were built in 1937-38 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1987. Initially known more as a landscape painter, Mrs. Langsdorf began to experiment with art and science concepts after designing the Doomsday Clock. In the 1970s, she created a series of works inspired by electric circuitry and nervous system synapses, and worked with Mylar. In the 1980s, she tapped into the tradition of archaeological site drawings in her drawings of the Precinct of Mut at Luxor, a project undertaken with the sponsorship of the Brooklyn Museum. In 2002, Mrs. Langsdorf collaborated with (art)n, a group that produced large 3-D images viewable without glasses, combining technology with American landscape traditions and social awareness. ( An exhibition of Mrs. Langsdorf’s artwork, titled “Works on Paper and Mylar, 1967-2012” will be on exhibit at the Printworks Gallery in Chicago, from May 3 through June 8. Mrs. Langsdorf’s husband died in 1996. “They collaborated in every aspect of their lives, always bringing out the best in each other,” Schweig said. “It was an interesting mix of physics and art.”