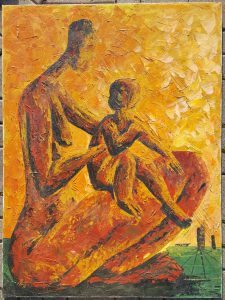

(Click to Enlarge)

Oil on Canvas

48 x 35 3/4 inches

Signed Bill Ross lower left

Vertical tear upper left

Chicago origin

Bill Ross, 58, Painter Who Saw Both Success, Disappointment In Art

January 31, 2001|By James Janega, Tribune Staff Writer.

Bill Ross, 58, who quit school as a teen to become an artist and who experienced both acclaim and frustration for the rest of his life, died Saturday, Jan. 27, of cancer in a southwest suburban nursing home.

His youthful decision led to prizes and trophies from Chicago art fairs, oils sold through galleries, exhibits at banks and hospitals, and murals painted on buildings across the South Side.

It also led to nights sleeping in doorways and flophouses, and stretches of time when, disappointed by the art business, he didn’t paint at all.

Mr. Ross, a gentle and cheerful man, was dedicated to his artwork and trusting to a fault.

“He used to say he never expected to be recognized for his talent. He just wanted people to be able to see things as he saw them,” said a former wife, Julia Ross. “He wanted to show them there was more than one way to look at things.”

The Arkansas native grew up near the Cabrini-Green public housing complex and was recognized for his talent first by winning a comic book “Draw Me” contest as a boy, and again during a grade school punishment. When his 1st-grade teacher consigned him to the cloakroom for being a class clown, Mr. Ross used a sculpting knives to turn a block of wood into mother and daughter giraffes.

“The school entered that sculpture in a contest, where it took citywide honors,” Mr. Ross told the Tribune in 1990. “After that, Mr. Davis, the art teacher, kind of adopted me.”

From his teacher’s art books Mr. Ross learned to imitate the styles of Degas, Renoir, Michelangelo and Van Gogh and, at 16, he dropped out of school to paint full time in a mass-production house. Soon after, though, posing as his own agent, he contrived to sell his artwork to hospitals, banks and other places.

In the 1960s and ’70s, his paintings were exhibited in office buildings and art fairs downtown. They were beginning to be picked up by dealers. He did paintings for churches and fashioned striking murals–including “Honor Thy Father and Thy Mother” at 6446 S. Ashland Ave.–that centered on African-American heritage.

“He did things that you look at and it touches you, tells a story,” his daughter, Bilesha Ross, said.

By the 1980s he was selling his work from a private studio and exhibited infrequently. He had agents, but paintings in their care disappeared, as did much of the money his art pulled in.

Embittered, he gave up art in favor of making signs and doing odd jobs, though he returned to painting in 1990 with renewed fervor. He was so single-minded while painting that he practically estranged himself from family members. Married four times, he proudly claimed to have 26 children.

He was always brightly optimistic about his work, excitedly relating his projects to his children. He was surrounded in recent years by a cortege of art students as he traveled around the country, mixing artistic work and renovation jobs. Though in recent year he had been rehabilitating buildings in Chicago, he had also done murals in Roseland, his family said.

Mr. Ross is also survived by four sisters, Maggie Ross, Willie Emily Jackson, Emma Henry and Frankie Gonzales; a brother, Jerry; and many grandchildren.

Plans for services have not been completed.

Source: Chicago Tribune